Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Exhibition

Neue Galerie

This event has ended.

Neue Galerie New York will open “Ernst Ludwig Kirchner,” a major overview of the great German artist’s oeuvre. The presentation will span from 1907 to 1937, presenting several distinct phases associated with the primary cities where he lived and worked: Dresden, Berlin, and Davos. This exhibition is unprecedented in its focus on Kirchner’s revolutionary style, which evolved in relation to his subjects and changing circumstances. Arguably the most outstanding German artist of the early twentieth century, Kirchner occupies a special position in the Neue Galerie collection, and this exhibition pays tribute to his inventive genius.

On view through January 13, 2020, the show will concentrate on Kirchner’s use of color, demonstrating the exciting dialogue that exists between his works in different media. Far from accepting the traditional hierarchy that placed fine art at the pinnacle of an artist’s achievement, Kirchner compared his activity in these various fields to “a tightly woven, organic fabric, in which process and completion go hand in hand and one aspect drives the other on.” The presentation will unite paintings, decorative works, drawings, and prints, and is comprised of loans from public and private collections worldwide.

DRESDEN (1905-11)

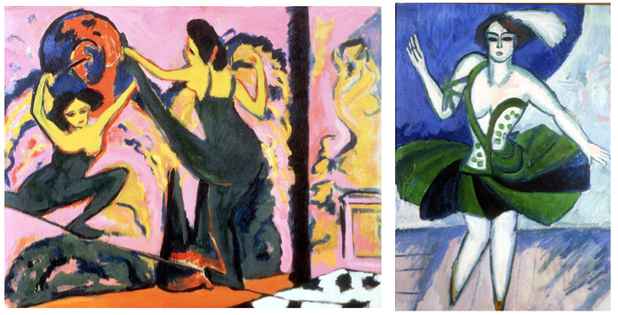

The exhibition begins with Kirchner’s Dresden period, examining how the artist used unusual variations of vibrant complementary colors to depict the world around him and to infuse the art of his time with a celebratory sense of renewal. A founding member of the Brücke (Bridge), Kirchner was part of a group of German Expressionist artists that discussed art and studied nature, rejecting prevalent academic styles. He described himself as a “Farbenmensch” (color person) and regarded color as key to his art. In a letter of 1923 the artist explained that color was the fundamental building block of his paintings. The earliest paintings in the exhibition, such as Portrait of Hans Frisch and Two Nudes (both 1907), demonstrate Kirchner’s fusion of various aspects of post-Impressionist style, including the use of pure impasto colors, sometimes squeezed directly from the tube, with areas of virtuoso decoration, such as the brightly patterned rug and armchair that frame the figures in these paintings.

In Kirchner’s large-scale pastels, he fused the expressive effects of color and line, while in his prints he introduced colored papers to achieve vivid overall compositions. The particular combination of benzine and wax is very specific to Kirchner’s work; it allowed him to achieve fast-drying, luminous, matte surfaces, which he kept unvarnished. Through these innovative techniques, Kirchner set out to “modernize” traditional genres like portraiture, the nude, and landscape painting. He also matched his new techniques to consciously modern subjects, such as his depictions of cabaret, urban landscape, and bathers.

BERLIN (1911-14)

In Dresden, Kirchner often took inspiration from the seedy, industrialized areas of the city rather than the splendors of its Baroque center. His move to Berlin in late 1911 intensified his awareness of the artificiality of city life and the psychological effects of metropolitan living. Kirchner’s palette became more tonal in response to grittier topics inspired by big-city life. Likewise, his paintings begin to incorporate graphic features associated with his drawings and prints. In comparison to the radiant colors of his Dresden paintings, Kirchner’s palette in Berlin is more subdued and often limited to a dominating color. Kirchner’s experimentation with color can be seen in two paintings of the same view from his Körnerstrasse studio, which was situated on the fifth floor of an apartment looking down on the Friedenauer Bridge and the Wannsee railway track. View from the Window (1914) shows Kirchner’s radical new perspective on the city, where tram and train lines crisscross barren architectural wastelands punctuated by advertising slogans etched onto blank facades.

THE WAR YEARS (1914-18)

Kirchner’s idyll in Berlin was brutally interrupted in August 1914 by the outbreak of World War I. He volunteered to serve in the mounted artillery, but in September 1915 suffered a mental and physical breakdown during military training. By this time Kirchner was drinking large amounts of absinthe. For three years, Kirchner spent extended periods in sanatoriums. However, his extreme fear of losing his identity as an artist in army service did not subsume him; rather it gave rise to some of Kirchner’s most powerful images. His color woodcut series Peter Schlemihl’s Wondrous Story (1915) is a displaced self-portrait and meditation on identity that recounts the artist’s sale of his shadow to the devil. Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915), one of the most compelling images in the artist’s entire oeuvre, depicts the artist in his soldier’s uniform with an imaginary severed painting arm. Kirchner’s gangrenous stump stands out against the Prussian blue of his uniform in glaring, complementary red and green hues. Kirchner’s powerful work from the war years, which reflects the artist’s identity crisis, combined tonal variations of color with jarring color contrasts.

DAVOS (1918-38)

In 1918, Kirchner began to spend extended periods in Switzerland, attracted by the health-giving air and light of the mountains and the stabilizing influence of life in a close-knit farming community. A carefully selected group of work from Kirchner’s Swiss period presented in the exhibition demonstrates how painting and printmaking converged in the highly original painterly prints and graphically charged paintings from the artist’s later years. The intense colors in these paintings are perhaps best interpreted as a combination of dream and reality: just as stage spotlights lit the cabaret subjects that Kirchner painted in his Dresden years, the moon above the Alps in Davos acts as nature’s own spotlight, dramatizing and intensifying the colors that haunt the artist’s imagination. Indeed, when he did sleep, the artist’s dreams were of color: “I dream… blue against blue, yellow green, red, purple… moonlit mountains… olive green, pink, blue and black, purple brown shadow tones, and ochre.” Another decisive factor in Kirchner’s Davos years was the impact of working together with the Swiss textile artist, Lise Gujer, on colorful tapestry projects. The exhibition includes two examples of Kirchner’s tapestry work, one made in collaboration with the artist’s lifelong partner Erna Schilling, and one made with Gujer. This interaction gave way to the so-called “tapestry style,” evident in paintings such as White House in Sertig Valley (1926), which combines large planar areas of color with smaller, closely interwoven color planes in a decorative, tapestry-like panorama. The change in technique reflects a shift in Kirchner’s ambitions: no longer concerned with capturing the sensory moment, as he was in his Dresden years, nor with reflecting the sophisticated nuances of urban experience, as he was in Berlin, Kirchner now creates monumental, decorative images that symbolize his visionary world view.

Nevertheless, with the rise of the National Socialist Party, in 1933 Kirchner’s work was branded as “degenerate art.” The changing political climate had an intensely negative impact on the artist’s health and disposition. In 1937, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition took place in Germany, featuring over 30 works by Kirchner. Meanwhile, over 600 works by Kirchner were removed from museums and either sold or destroyed, and he was expelled from the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. Kirchner’s health declined, and he fell into a personal crisis, ultimately committing suicide in the Swiss Alps in 1938.

Media

Schedule

from October 03, 2019 to January 13, 2020