“YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION: American Artists and the Communist Party” Exhibition

Galerie St. Etienne

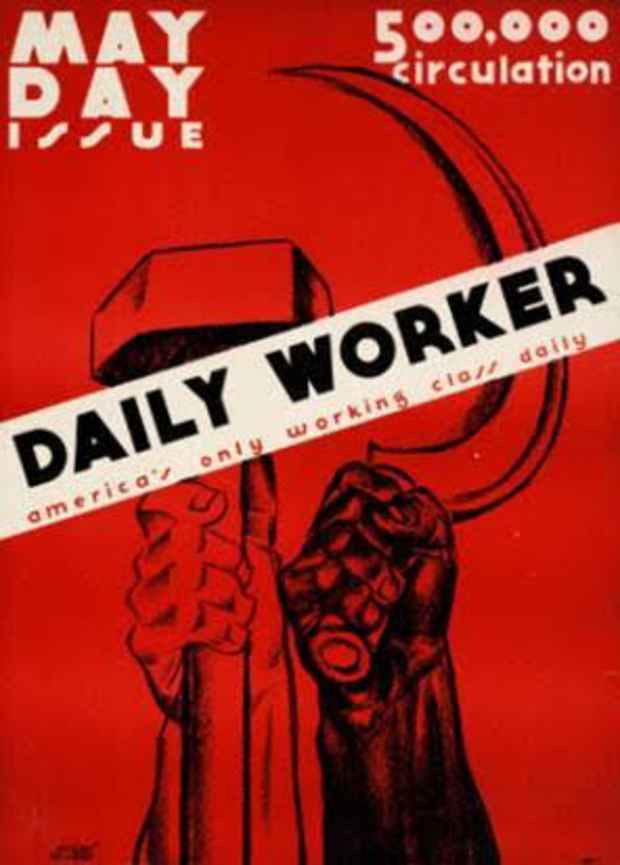

[Image: Hugo Gellert "May Day Daily Worker" 1930s or ‘40s Lithograph poster in black and red, 16 7/8 x 12 in.]

This event has ended.

YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION: American Artists and the Communist Party on view at Galerie St. Etienne, October 18, 2016, through February 11, 2017, explores the relationship between artists and politics in the 1930s and 1940s. The exhibition features leading American artists who sought social change and economic stability during and after the Depression, such as Leonard Baskin, James Daughtery, Stuart Davis, Phillip Evergood, Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, Jack Levine, Louis Lozowick, Alice Neel, Ben Shahn, Raphael Soyer, and Lynd Ward. More than 60 paintings, drawings, watercolors, lithographs, woodcuts, and posters are on exhibition. Drawings and gouaches by Sue Coe, a contemporary New York-based artist who deals with today’s issues, will hang next to work that has provided her inspiration.

On November 3, 2016, at 6:30 PM, Amei Wallach, the journalist, art critic, and filmmaker, will join gallery director Jane Kallir in a discussion about the exhibition to be held at the gallery.

YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION is organized into six prevailing themes: Fat Cats and Workers (Capital and Labor), The Unemployed, War and Peace, Race, Demonstrations, and The Democratic Process.

Three works by Stuart Davis are among the exhibition highlights, including a pen and ink study for Men Without Women, a mural commissioned in 1932 for the men’s lounge of Radio City Music Hall. (In 1975, the mural was painstakingly removed and donated to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.) The title of the work (which Davis himself disliked) is a reference to the “masculine” world of smoking, gambling, motoring, sailing, and barbershops. Also shown is a study, made in 1932, for the oil painting Men and Machine, which is now in the permanent collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Davis added politics to his life at the onset of the Depression, advocating that artists collectively address their financial insecurity by demanding government patronage. He was one of the founders, along with Hugo Gellert, Louis Lozowick, Ben Shahn, and Lynd Ward, of the American Artists’ Congress, which implored artists to unite against war and fascism, a mounting threat to artistic freedom and culture.

Alice Neel is represented in the exhibition by a rare,early oil loaned by her estate, Longshoreman Returning from Work (1936). Neel, a member of the Communist Party, became politicized after joining the Artists’ Union, whose president was Davis.

Other exhibition highlights include:

Sacco’s Family After The Verdict, by Ben Shahn, is one of 23 gouaches that comprise the artist’s famous series, The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, circa 1931-1932. The series is based on the infamous trial of the reputed anarchists, Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, whose execution in 1927 sparked protests in America and abroad over charges of ethnic persecution.

Granite Quarry (1936), by Louis Lozowick exemplifies the artist’s sympathy with the American working class. Lozowick employs a low vantage point that endows the laborer with heroic significance. The Communist Party encouraged artists to glorify the worker, rather than depicting him as a downtrodden victim.

With Renunciation, 1946, one of Phillip Evergood’s most noted paintings, the artist pursued his long history of activism into the atomic age. Like many of his contemporaries, Evergood was now concerned with America’s preparation for annihilation. Following the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and continued testing in the Bikini Atoll, he conceived an image portraying a post-atomic world in which the destructive power of the bomb ushers a return to the beginning of time. The mushroom cloud rises, civilization goes up in dust, and only our evolutionary predecessors, the apes, survive.

Background

In the early 1930s, America’s leading artists responded to the socio-economic devastation of the Great Depression by mobilizing for political change. Believing that capitalism had failed, many were attracted to the socialist experiment then being conducted in the Soviet Union. Although not all artists joined the Communist Party, most were members of the American Artists’ Congress, which was part of the “Popular Front” initiative launched by the Communist International (Comintern), and whose president was Stuart Davis.

Mainstream institutions like the Museum of Modern Art supported the work of such “radicals” as William Gropper, Ben Shahn and Hugo Gellert, despite opposition from some of its trustees. Left-wing artists also received support from the U.S. government, which employed many of them through the programs of the Works Progress Administration.

After World War II, art became part of the government’s arsenal in fighting the Cold War. America’s cultural elite rejected representational subject matter and its left-wing associations, instead promoting the ostensibly apolitical work of the Abstract Expressionists as a beacon of democratic freedom. Gropper and kindred artists were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and banished from major museums. Ben Shahn sought refuge in the world of illustration and advertising. Leonard Baskin, who feared being compromised by commercial influences, fled to rural England. For Shahn, Baskin and later for the British-American artist Sue Coe, publication became outlets for political content that was no longer permissible in the “high” art arena.

Media

Schedule

from October 18, 2016 to February 11, 2017

Artist(s)

Stuart Davis, Alice Neel, Raphael Soyer, et al.