"Can I Get a Witness? Working from Observation" Exhibition

steven harvey fine art projects

This event has ended.

Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects is a long and narrow space, somewhere between a bowling alley and a railroad apartment, on the Lower East Side. It is within this rather confined space that Marshall Price, curator at the uptown National Academy of Art, installed 11 paintings by artists committed to working from observation. Chronologically, the artists span five decades (or generations), with Lois Dodd and Lennart Anderson, born respectively in 1927 and 1928, being the oldest. The youngest include Gideon Bok, Anna Hostvedt, Sangram Majumdar and Cindy Tower, with Bok and Tower born in the 1960s, and Hostevedt and Majumdar born in the 1970s. The other artists are Susanna Coffey, Rackstraw Downes, Stanley Lewis, Catherine Murphy, and Sylvia Plimack Mangold, who were born between 1938 and 1949. Together, these artists — a number of whom have been influential teachers — suggest that observational painting is a vigorous, various, and imaginative enterprise that continues to fly under the radar....

The first painting I saw — and the oldest in the show — was “Madison, Maine” (1966) by Lennart Anderson. Through his use of silvery grays and a muted palette, Anderson is able to evoke the particular nondescript New England light spreading across a mill, a landscape and a river, reflecting the overcast sky above. His placement of horizontals and verticals adds a geometric structure to the painting, which the reflection intensifies. It’s as if the factory is supported by the river, which, in fact, it is.

Anderson studied with Edwin Dickinson (1891–1978), one of America’s great painters committed to working from observation. Dickinson’s quick oil sketches or “premier coups,” as he called them, usually done on site between two and five hours add up to a wondrous body of work that still remains both unrivaled and largely unknown to the wider public.

John Ashbery, who has written beautifully and incisively about Dickinson, made two points that came to mind while looking at this exhibition. The first was that Dickinson was able to make “eeriness and vivacity seem to go hand in hand, as they do in our social life.” And the second point that Ashbery made has the ring of a deeper truth: ”Few painters would have seen any possibilities in this dour patch of landscape, but he transforms it into something unforgettable.” By transforming the severe into the memorable, the painters in this exhibition take something unlikely from the world, as well as give something even more unlikely back to it. It is this kind of seeing — one that amounts to an almost moral commitment — that holds the exhibition together.

(I wonder if observational artists, in their devotion to the fleeting and the insubstantial, to states of destruction and decay, and to the ordinary and repetitive, are the materialist equivalent of the Buddhist Yun Men who declared, “Every day is a good day.”)

I have written about a number of these artists before, often more than once — Lois Dodd , Rackstraw Downes, Sangram Majumdar , Sylvia Plimack Mangold , and Catherine Murphy. It is the artists that I haven’t written about previously that I largely want to comment on.

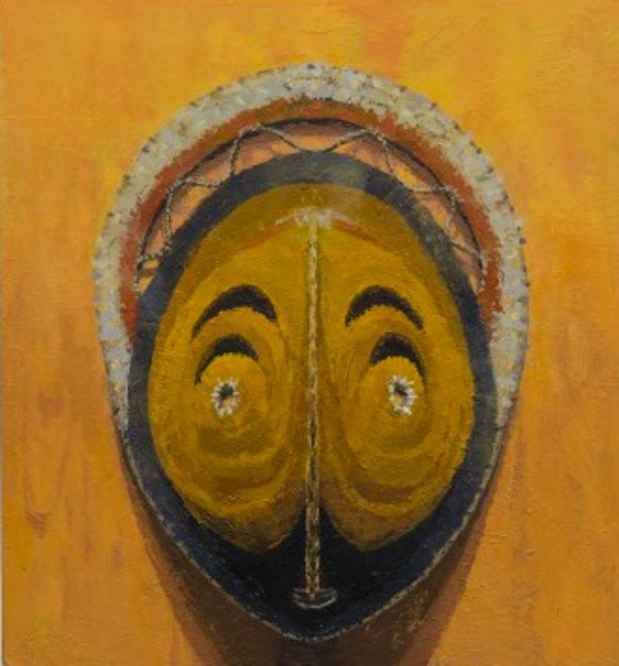

By depicting an ochre New Guinea Yam cult mask against a mustard yellow ground, Susanna Coffey suffuses her painting with a yellow light. Working with a restricted palette, Coffey elevates her subject into a realm of otherworldliness that seems consistent with the mask’s original function. I suspect that Coffey believes that painting can also possess a talismanic power, that it is not simply the result of logical decisions.

Anna Hostvedt, “Windward at 335 (degrees)” (2007), oil on panel

Anna Hostvedt paints parking lots that are even more nondescript than what we might expect from such drab, functional spaces. They are the kind you typically find adjacent to a commuter train station, a parcel of land framed by a row of evenly planted trees. Like so much else in our lives, they are places to be used, but not looked at, much less thought about.

Hostvedt can convert familiar dullness into a weird painting — it is a parking lot, after all — but she has made this unpromising subject fascinating and incongruous. Do we simply look for our car and leave? Or do we actually look at the different views from outside and inside this space? Why is there only one maroon-colored vehicle in the lot? Is that color a sign of the only individuality that we can attain in this conformist world?

Hostvedt can convert familiar dullness into a weird painting — it is a parking lot, after all — but she has made this unpromising subject fascinating and incongruous. Do we simply look for our car and leave? Or do we actually look at the different views from outside and inside this space? Why is there only one maroon-colored vehicle in the lot? Is that color a sign of the only individuality that we can attain in this conformist world?

Gideon Bok, “The Brief but Epic Battle Between the Great Jones and Little Bermuda” (2007), oil on linen, 66 x 37 in

The deep space, mirrored images, odd angles, and flattened planes in Gideon Bok’s painting of a room suggests that he has painted (and remembered) it and the events taking place in it from different points of view. On one side of the painting a girl is looking at a computer, while a television faces a group of friends gathered on a blue couch. Are the same people also sitting on a tan couch on the other side of a coffee table? In the foreground, a map lies on the floor, anchored by the record jacket of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, which contains such classics as “Like a Rolling Stone” “Desolation Row,” and “Highway 61 Revisited.”

And yet, while Bok might be diaristic and include all sorts of details, I don’t feel that he is trying to tell a story. He is too interested in the space and the things in it, the flow of people through the room, to try and make a single narrative. Bok isn’t a detached observer, but a participant and therefore not omniscient. The deep space seems at once inaccessible and open to scrutiny, like our lives. The map suggests that we need help finding our way around even the places and things we think we know.

Cindy Tower, “Maintenance Walk” (2010), oil on canvas, 60 x 60 in

This is the first time I have seen a painting by Cindy Tower and I became an instant fan. Some works creep up on you slowly, while others hit you in the solar plexus with such convincing force that you wonder how you could have ever missed this artist’s work. Such is the case with Tower. Her large painting, “Maintenance Walk” (2010), is dense with decrepitude.

At the same time — and this part is as unsettling as it is bizarrely exhilarating — part of the pleasure the painting delivers is the artist’s heightened, almost hallucinatory attention to detail, from the crisscrossing rows of overhead pipes to the rusted and defunct machine parts littering the entire factory floor. You are not quite sure what to think.

Everywhere you look you see something rusted and eroding, in a state of extreme neglect, more evidence of America’s long, agonizing decline. She uses oil paint (or a mixture oil and finely ground dirt) to depict dirty, often greasy things. As can only be done in painting, Tower slows down the decline — she asks the viewer to look at everything and to ponder what such ample disintegration might mean.

At the same time — and this part is as unsettling as it is bizarrely exhilarating — part of the pleasure the painting delivers is the artist’s heightened, almost hallucinatory attention to detail, from the crisscrossing rows of overhead pipes to the rusted and defunct machine parts littering the entire factory floor. You are not quite sure what to think.

Everywhere you look you see something rusted and eroding, in a state of extreme neglect, more evidence of America’s long, agonizing decline. She uses oil paint (or a mixture oil and finely ground dirt) to depict dirty, often

greasy things. As can only be done in painting, Tower slows down the decline — she asks the viewer to look at everything and to ponder what such ample disintegration might mean.

Sangram Majumdar, “Paper Repositioned” (2012), oil on paper mounted on panel, 51 1/2 x 55 1/4 in

Originally, I had not intended to write about Sangram Majumdar’s painting, “Paper repositioned” (2012), because I have written about his work before. However, shortly after finishing what I thought was the final version of this review, it occurred to me that Majumdar’s painting — which hovers precisely and deliberately between representation and abstraction without ever coalescing into either one — eludes legibility, but just barely. Only a masterful artist can get to such a disquieting place, which firmly pushes back against seeing. We must look and look again before we can even begin to see it. On the other end of the spectrum is the startling clarity of Tower’s “Maintenance Walk.” By learning from abtraction — from allover abstraction to minimalist repetition — the artists in From Life were able to make their paintings fresh.

From Life is a large group exhibition in which no one struck either a ham-fisted or frivolous note.

Is America’s legacy — after a little more than five hundred years — going to be that we did our level best to turn a blossoming continent into a land of abandoned factories, empty missile silos, decaying granaries, dust bowls and dreary parking lots? And what about Maintenance Walk? Neither the immortality of great art nor the requirements of fitting into a scene seem to be of much concern to Tower, because her most urgent issue is to look carefully and clearly — to be true to what is seen. Such ambition is refreshing.

Media

Schedule

from November 14, 2012 to December 23, 2012

Opening Reception on 2012-11-15 from 18:00 to 20:00