“Unseen Works: David Hammons and Friends” Exhibition

Tilton Gallery

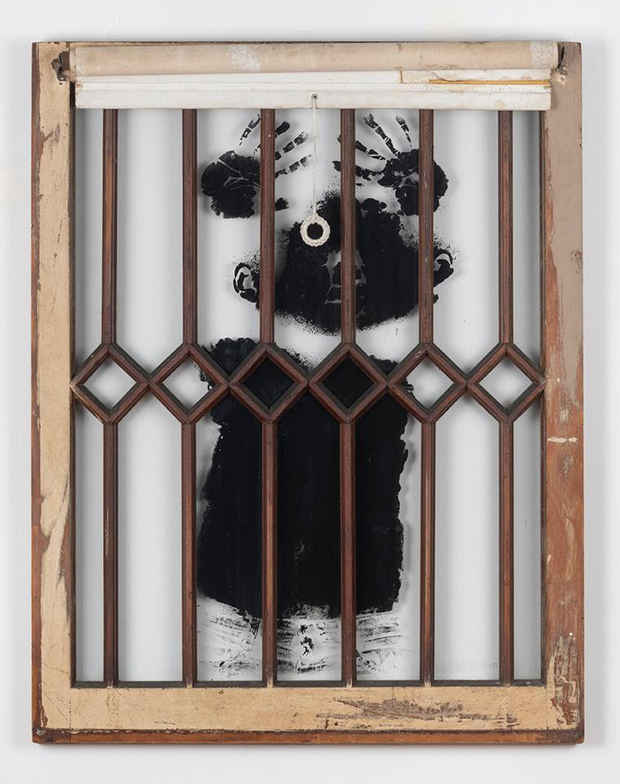

[Image: David Hammons "Black Boy's Window" (1968)]

This event has ended.

Tilton Gallery is thrilled to present an exhibition of Unseen Works: David Hammons and Friends.

Unseen Works presents a selection of works that have not been viewed in public for many years, some not since the early seventies, and in some cases, ever. Central to the exhibition is a 1968 work by David Hammons, Black Boy’s Window. Building upon this sculpture are a number of Hammons’ body prints dating from 1969 to c. 1975, all made while he was living in Los Angeles. Works by a few of Hammons’ friends and colleagues, also largely unseen in New York, accompany the Hammons. These include early works by Noah Purifoy, John Outterbridge, Timothy Washington, all colleagues from Los Angeles, and Ed Clark, living in France at the time.

In Black Boy’s Window, one of Hammons’ earliest iconic sculptures, the artist transforms a window, salvaged from demolished housing in the neighborhood near USC in South Los Angeles; it is a beautifully structured wood frame in itself, with a distinct configuration of ornamental crossbars. Hammons removed the many panes of glass in order to silkscreen a body print onto one side of each and then returned the glass panes into the frame. The black ink image of a boy, hands raised to his face, peers through the multiple panes of glass, his face and body interrupted where the frame intervenes. He is clearly on the outside, the more privileged viewer on the inside, implicated in the act of not letting the boy in. The original window shade remains attached, suggesting that at any moment the viewer could pull down the shade, further shutting out the boy. This work relates closely to the more widely known The Door (Admissions Office) of the same period, in the collection of the California African American Museum. Here a similar figure peers through the glass window in a free-standing wooden door on which is stenciled “Admissions Office,” again shut out. The powerful figure in both these works is clear, yet abstracted, the body truncated, all focus on the head and hands, and becomes a stand in for all who are excluded, poignant commentary on the state of African Americans in American society. The work also relates to Betye Saar’s Black Girl’s Window, and to a series of works begun in 1966 for which she used old window frames to hold her images; the two artists were good friends and colleagues.

Around the pivotal work of Black Boy’s Window, we have assembled a group of body prints on paper or board that follow the varied manifestations of Hammons’ manipulation of this very personal, performative medium. The process of creating the body print required a high degree of planning, and all meaning and symbolism is carefully thought through. In one highly unusual work, the body print itself - another densely printed image of a truncated figure - is cut out from its sheet of paper and sandwiched between two layers of Plexiglas that are cut to take the figure’s shape, thus becoming as much an object hung on the wall as a work on paper.

Other body prints vary from single figures in various postures to double figures; from frontal, more confrontational images to subtly manipulated side views; from delicate prints highlighting the textures and patterns of both facial hair and clothing, to complex collages incorporating cut out sections of wallpaper. “Puzzle” pieces reflect the artist’s view that for a black person, living and making one’s way in this world is a puzzle. Boy with Flag questions the relationship between the black individual and the American flag, with all it stands for, confronting once again the issue of exclusion. Well known through reproduction, but not seen in New York since 2006, this work incorporates a silkscreened full color flag covering the left vertical half of the image. A black figure filling the right half of the page emerges from behind the flag to hold equal weight on his side of the image.

These body prints, made while Hammons lived in Los Angeles (from 1963 until approximately 1975), come out of a period in that city with immense creativity as well as political ferment. This was a time when black arts organizations were being formed, black owned galleries such as the Brockman Gallery, Suzanne Jackson’s Gallery 32 and The Gallery (of Samella Lewis) were opening; artists were participating in the black arts movement that also included the music and literary worlds. This time period spans the 1965 Watts Rebellion, a powerful, historical and life changing moment. Protests took place outside of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in a push to make that institution show more black artists. Assemblage, the re-use of found objects, was explored by a number of artists, black and white. This was when Ed Kienholz, also working with assemblage, made political sculptural installations such as Five Car Stud and Backseat Dodge. Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters and Robert Rauschenberg all had solo exhibitions at the Pasadena Art Museum in the early to mid-sixties. Black artists embraced assemblage on multiple levels. The repurposing of worn and discarded materials was part of the heritage of many artists, as was the need for cheap or free art materials, but assemblage also made a political statement, while simultaneously speaking in tangent with the Dada and conceptual art movements.

For this exhibition we have assembled a few particularly significant works by some of Hammons’ closest colleagues. These include an early work by John Outterbridge, Jive Ass Bird, 1971 from the Rag Man Series, a group of works that have largely gone missing. A 1966 Noah Purifoy, Drum Song, one of his 66 Signs of Neon sculptures, this one incorporating melted neon from the remains of the destruction that occurred in the August 1965 Watts Rebellion and from which the subsequent exhibition 66 Signs of Neon derived its name. The majority of these works have also gone missing or have been destroyed. Timothy Washington, perhaps more literal in his imagery, but equally poetic and symbolic, is represented by one of his early etchings on aluminum with mixed media, Why, 1971. As with most of his work of the period, this piece challenges accepted views. Ed Clark, a New York Abstract Expressionist who lived much of the fifties and sixties in Paris to escape the racism in America, pursued abstraction while being consciously political, and is here represented by two magnificent unseen paintings from 1968.

Media

Schedule

from February 26, 2019 to April 20, 2019

Opening Reception on 2019-02-26 from 18:00 to 20:00