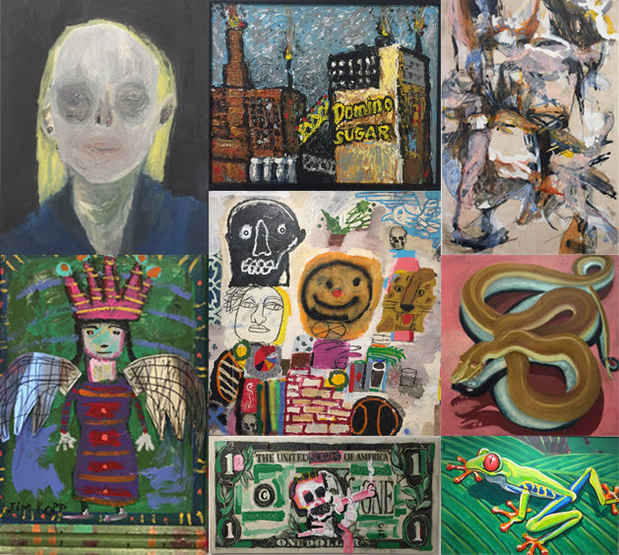

“All Art +: Brilliant Disguise” Exhibition

Van Der Plas Gallery

This event has ended.

All art is artifice, we’re often told, yet Picasso said that art is the lie that tells the truth. In a gallery filled with eyecatching work that can mislead or seduce, how do you find the true nature of the artist? In this new iteration of All Art +, Adriaan van der Plas invites an array of personalities to reveal an essential truth about themselves. In the spirit of the season, some of them are wearing masks. The question is, which ones?

Alli Wolf’s lyrical portraits of heroines make the task of conquest seem easy. Her “Kraken” depicts a contemporary mermaid in carefully-blended tones of cool blue and lavender. Lovely, yes, but what does an alluring sea creature have to say to her audience in the gritty Lower East Side? That the generosity of nature might give a gift of beauty—but that gift might be a tease.

Joe Bloch likes thick and crude painted surfaces, industrial subjects, and dark jokes. His wisecracking view of the reaches of Brooklyn that he calls home can be ironic and gloomy. Yet this painter-cumentrepreneur is a nurturer and protector too, and has put a considerable amount of time into fostering and promoting the work of obscure and soon-to-be known artists. Is he optimist or pessimist?

People who follow the continuing careers of downtown artists probably know Fred Gutzeit as the inventor of a kind of calligraphic painting based on signatures. It can be loopy as pasta on a plate, and seems to come easily to this self-possessed, experienced artist. In the sculptural wall piece called “Cokehead,” though, we see a fragmented face that seems to barely contain its despair. Did the artist make this transition from sinner to master himself, or is this a reference to the East Village’s painful past?

Jim Kopp calls himself a self-taught painter. His “Dark Age Girl,” a lumpy assemblage made mostly of painted wood, has a scratchy and frontal look that is many people’s definition of childish. Almost all his work shows animals and children staring back at the viewer from the center of the picture plane, or nearby, as if there weren’t any alternative. Before you decide this is a simple-minded exercise, consider the effect of the subject’s gaze. Do you see intense focus, and a sense of calm that overwhelms you? There’s something here that’s wise beyond its years.

Dan Freeman seems to appear and disappear in the painting world, according to no particular schedule: he’s like a comet that visits on the eve of important (but not always happy) events. Claiming kinship to van Gogh and Caravaggio is a bit of a stretch when it comes from someone who reminds people of a mad cartoonist. And Freeman’s fine eye may seem at odds with his loud color and rubbery line, but it brings him right into the same room with his other inspirations, Alice Neel, Alex Katz, and Red Grooms. This painter seems to work in a free and open space without a net, particularly here, with his glistening painting “El Coqui.” Is there a sense of frustration behind his boundless energy? Look closer for a real painter’s paradox.

In contrast to Freeman, who is in many ways the model of a social New Yorker, Kayo Albert is a sort of biologist in the studio. Asked for influences, she cites Abstract Expressionism and Carl Jung, and believes in an organic form of creativity that’s rather like having delicate roots growing in one’s head. “I imagine having an invisible rhizome nourished by memories, dreams, flashes of images and ideas stored deep under the ground,” she says. Among those in this show, Albert might be the most mysterious. This evanescent sense of connection is at odds with her method, a delicate and disciplined brushwork that whispers a great deal about the formal history of abstraction as well as the sacrifices artists make.

There is, in fact, a great deal in this show that’s not what it seems at first glance. If Polly Cook’s “Dream A Little Dream Of Me” is a romantic fantasy, what is that sad figure lurking in midplane trying to say? If Chris Dacs is as carefree a trickster as he’d have us believe, why does his work seem to regard its own viewers with a critical stare? Then there’s Liam Kotti’s “Happy Face Plastic Bag,” either a friendly acknowledgement of an everyday item or a furious indictment of the society that produced it.

Konstantin Bokov’s work itself is uncritical, it seems. Bokov is a kind of blithe spirit who collects artifacts on the New York streets and turns them into urban archaeology. Now, however, he’s showing a Humpty Dumpty collage that looks like it could be a commentary the fragility of art trends. This work, in fact, looks like a fractured Keith Haring. Literally fractured: the linework is in pieces, as if it crashed into the dour tenement buildings in the background. Can it be that in a fight between art and real estate, real estate always wins?

Among the remaining artists, Carla Caletti alone might have figured out how to exist in two worlds at once. Her daubed paintings of urban street life depict people in an unforgiving landscape, yet the subjects move in an atmosphere vibrating with molecules of lifegiving color. What would she say to Sally Eckhoff, whose brightcolored animals always seem on the road to destruction? In a meticulous painting of two snakes wrestling on a pink background, the subjects are smiling, but their shadows tell another story. The snake on top is still grinning, while the one underneath holds its mouth open in a scream.

What accounts for the discrepancy between the figure and its aftereffects? “Politics,” the artists says. “The story is power.” Whether vital or fatal, sometimes it’s only the illusion that’s real.

Media

Schedule

from October 16, 2017 to October 31, 2017

Closing (Halloween) party October 31 at 4-8 pm

Opening Reception on 2017-10-18 from 18:00 to 20:00