Joshua Abelow Exhibition

James Fuentes LLC

This event has ended.

At Allen & Eldridge is located below James Fuentes at 55 Delancey St.

Allen & Eldridge presents a solo presentation of drawings by Joshua Abelow. They represent nearly a decade of works, most of which have never been exhibited.

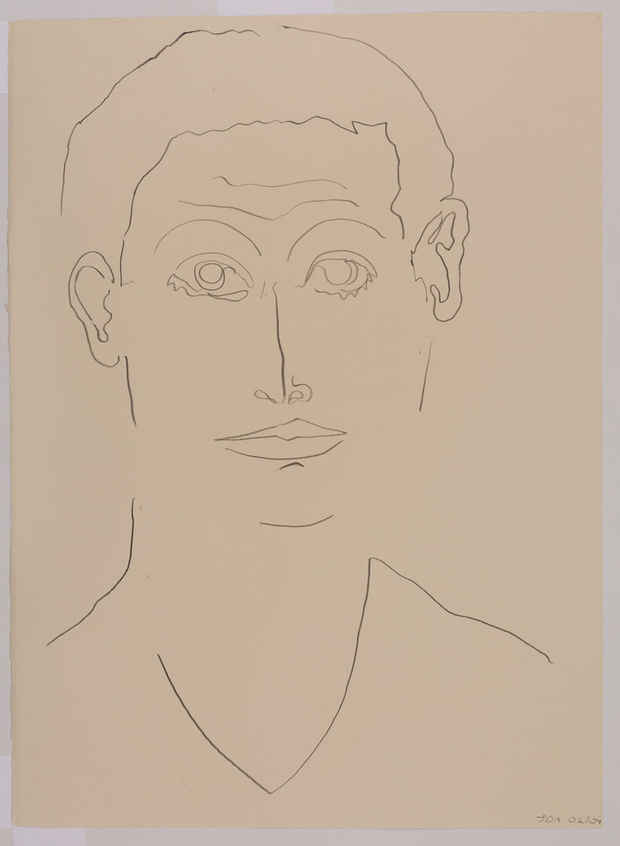

The first thing you will notice about Joshua Abelow’s drawings—and not just their auspicious beginning, but all the way through, through several permutations—is that the figures are all head, head more than face, or look, or expression. In fact, most are empty of what depicts the person, despite the omnipresence of the head; negating any idea of this as a work of portraiture. The lines, delicate though they may be at times, contribute to the head’s bulk, its seat at the top of the trunk, its imposing existence and weight. It is as if the head directs the lines of its own making in an act of self-generative, ex nihilo cloning.

Made of these lines, their culmination, but somehow still before or behind. I am fascinated by the centrality of the head in Abelow’s drawings. Why the head? Why the inescapability of this head? And what force or fascination do these heads exert on their viewer? How does the sheer serial force of these drawings—over five hundred—leave us asking for more, not less; if indeed they do, and they do for me, so that like a public guillotine, we demand additional heads? Give me head.

The head is not only the symbol of mind and life and rationality, the apex of the organism, arranged hierarchically, but also, its opposite, or other, death, kaput, finished or not working. Following the logic of part to whole, synecdochically, the head is removed, not only in the case of capital punishment—off with your head—but simply capital itself, whose main root, caput, means precisely this, one’s wealth, one’s lendable head. The head is what can be severed, as in heads will roll, or spent, as in bet your head. The accumulation of head.

So, we enter into the head count, as if heads and counting went hand in head. This is an act always first animal, as in to tally one’s cattle—Abelow must know this—transmuted by the state into all those heads imprinted on coins. So the head is the leader, the sovereign head, and the leader is the one who can decapitate himself, lend you his head—another version of giving head—include you in the head count. Lenders create borrowers, and can recall their heads, along with some of yours, your debt to the head. Head creates more head.

Capitalism in this vein, it has been said, is inescapable. Its logic is impeccable, a kind of oversize head that does not know its own ceiling, size, or shape, because where does the self-replicating head end? When does it stop? Capital punishment and the punishment of capital are united. In Abelow’s work this Faustian bargain—the appearance of the devil, usually along with the artist’s brush—seems linked to this impossible exchange.

This exchange of head is a rather funny, if not disturbing, way of thinking not only about what the capitalist must do, but also the artist. The Genius, The Artist, The Poet, The Painter, meets Mr. Critical, Mr. Brown Noser, Mr. Double Dick, Mr. Internet. Blog Blog Art Blog … Abelow, it must be said, seems to blow this exchange up by simply producing too much, breaking the head shop’s rule of supply and demand.

Finally, in this delirium, perhaps one encounters the desire to escape—and I will argue that Abelow attempts precisely this—the inescapable head. This is how I read the repeated plea of “help me”—me, me, me, me, me, head me—that appears towards the end of the oeuvre. Or even, “kill me.” A problem, one might argue, for any contemporary artist.

The horizon beyond the head emerges: what is over one’s head, beyond comprehension. Indeed, something found simply in the figure of madness, the head case, or the acephalic figure, the headless man, what it means to lose one’s head. Not an easy task. Abelow is to be commended. Because why all these heads in the first place, if not in the attempt to finally destroy or wear out its indelible mark?

Perhaps it is here that the erotic emerges, or the attempted counteruse of the erotic, something that also finds its place in Abelow’s drawings. After all, if there is something that rivals the head in his work, it is the genitals, the phallus in particular, and its many permutations. Its final overwhelming demand being—one more time, give me head.

So if the head is empty of the specificity of any given person in Abelow’s drawings, the person, like capital, is taken to its most extreme point of abstraction and made completely generic. It is here where we finally encounter sexuality—from the orality of smoking and drinking, to varieties of penetration, oral sex, masturbation, and the like—as something also generic but perhaps more critical.

Difficult to wed this with the head, but Abelow tries, an effort that extends into his stick figures that are all genital and head, like the two clumsy appendages of man. This was always Freud’s main contention, which I’m allowed to say with authority since I’m a psychoanalyst. Add to this the paintbrush. Or, the artist who stands on the heads of others. Sucks his own dick. Gets lost in his own mythology. Help me. Perhaps we might name this problem of the head—being all head—twenty-first-century solitude, as Abelow does in one particularly striking drawing.

One truth I have found in this body of work is that despite all the sex, the touching, the open arms, the superimposition of figures, and the assembly of heads, nothing meets. They gaze past one another, penetration happens between parts. Never two whole figures, never the two conjoined. The head is something that separates—irrevocably so.

And so much so, that, in the final series, with the head expanded more to the entirety of the body—the stick figure, the most anonymous of his persons, with the intense gyration that attempts to move into the surround, this movement composed of heavy staccato labyrinthine lines—it still feels like a force of continued separation, if not isolation. A protective bubble or sack, not unlike the head, and even if body, still in battle with it. I was happy to find medusa here, the ultimate head, the many-headed head, who reduces you to stone.

Maybe this is the truth of lines, really? Their force of division, separation, and isolation? Boundaries we can actually barely cross despite so much transgression and violence and acting out, despite so much exchange of head. And maybe this is the intimate link between line and head as the pure gesture of Abelow’s drawings?

We easily forget that drawings are composed of exactly this—lines—especially in our romantic whimsy in the face of art, our belief in human relationships, or fusion of feeling, and supposedly sublime beauty, even when grotesque, something Abelow has brought down low in his work, in every direction. Down to the lowest of whispers, in order to show us that what we are asking for, in asking for this, is, I promise for the last time, give me head.

▪ From ‘Give Me Head’ by Jamieson Webster

Media

Schedule

from October 07, 2016 to November 06, 2016

Opening Reception on 2016-10-07 from 18:00 to 20:00