LeRoy Neiman “40/40”

Franklin Bowles Galleries -New York

This event has ended.

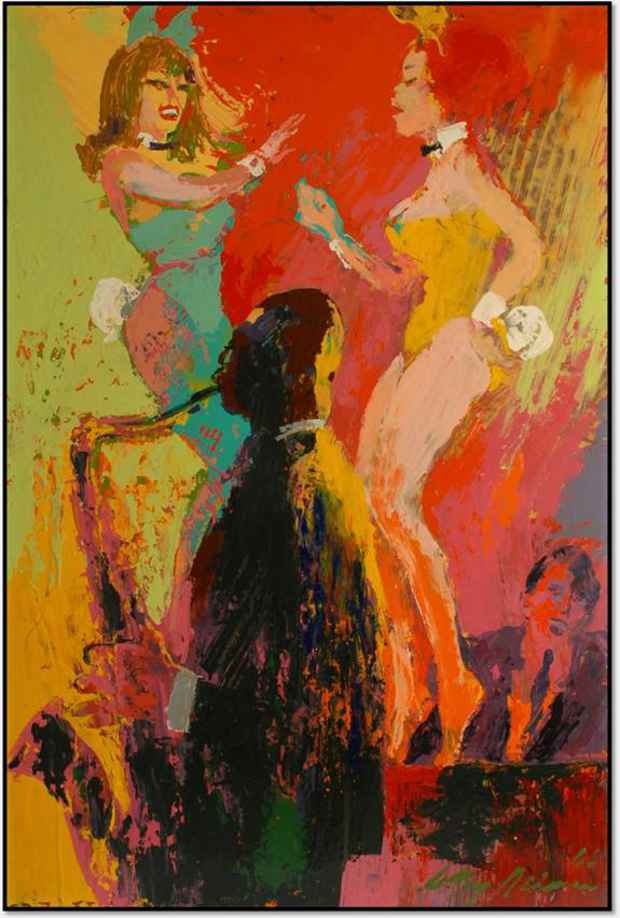

LeRoy Neiman was far ahead of his time. The very opposite of the detached, retiring artist, he was involved during his distinguished career in many developments that now constitute key aspects of the history of post-World War II art. He made representative art when the art world mostly deemed only abstract art acceptable. He updated the Impressionist breakthrough—the depiction of contemporary leisure life—but while the Impressionists painted middle-class leisure, Neiman took an innovative route, depicting celebrities and spectacles. Yet he often included ordinary people, the audience and workers who made the spectacles he was depicting possible. In so doing, he figured out how to adjust art for a media world where television made celebrities the currency of everyday life. Through his association with Playboy magazine, and friendship with Hugh Hefner, he played a key role in gaining social acceptance for art to depict female nudity as enjoyable and exciting without it needing to be attached to a religious or classical figure as in almost all previous art history. This is a huge list of achievements.

Contemporary Art is so tolerant and eclectic that we can easily forget how different the art world was that Neiman first encountered. Contemporary Art, the dominant category since the 1990s for classifying the art of our time, typically includes and welcomes the art produced by all artists still living or recently dead. By contrast, before Contemporary Art’s rise, it was often heated battles over new styles and their struggles for recognition that dominated, as in Impressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and Pop Art, in the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century. Each new style typically implied, or explicitly claimed in polemical fashion, that work done by artists in that style was superior to what other artists of the time were typically producing, a view often expressed in the context of a belief in an evolutionary progression of art.

Neiman entered the art world in the 1950s and characteristically refused to conform. A crucial axiom of many styles at that time, with Abstract Expressionism as the newest contender, was disdain for “representative art,” expressed, for example, in the claim that when people looked at and liked (“appreciated”) abstract art, their experience was higher quality—more creative, richer, thoughtful, sublime—than the experience of those who viewed representative art. This claim was never supported with any real evidence drawn from examination of people actually viewing art. Neiman recounts in his autobiography, All Told, how he resisted:

The style of the hour was abstract expressionism—Jackson Pollock, de Kooning, Franz Kline—but as hard as I tried, faces and figures would poke out at me from the surface of the canvas, saying, “Hey, look who’s in here, LeRoy, why are you trying to cover us up?” To hell with surrealism, futurism, or ab-exism! Even when I’d start a painting in abstract, there was a subject lurking: a face, a place, a scenario would seductively emerge…When I set out to paint realistically, I thought, “Now this really works!”…The art world I thought would be stunned. Figures materializing out of pools of color—who’d ever done that before?

Neiman filled the void left by the flight from representation by depicting contemporary leisure life. One of the most innovative aspects of the Impressionists was their depiction of middle-class leisure. As the art historian, Meyer Shapiro, writes, “It is remarkable how many pictures we have in early Impressionism of informal and spontaneous sociability—breakfasts, picnics, promenades, boating trips, holidays—these urban idylls…present the objective forms of bourgeois recreation in the 1860s and 70s.” Yet while the themes of the Impressionists, prescient and avant-garde in the nineteenth century, still appeal to modern audiences, much of their appeal is now linked to their value as records of an earlier age. It is in Neiman’s work that we can find arguably the liveliest, most creative, and most socially-aware depiction of the leisure life of the post-World War II decades. Further, he applied vibrant color in depicting this spectacular imagery.

Neiman was also in the vanguard of artists escaping what he dubbed “the old prewar [sexual] prudishness.” Until roughly the mid-nineteenth century, artists could generally depict naked women only if they were clad in antiquity or religion or were allegorical—called Venus, Sabine, Truth and so forth—to be acceptable. Even after that, until the era of Playboy and Neiman, female nudity could scarcely be depicted as a spectacle to be enjoyed. Neiman’s friend, Hugh Hefner, founded Playboy in 1953, and quickly installed Neiman as artist-in-residence, to depict the magazine’s mixture of thoughtful journalism and fun. Neiman’s first assignment was illustrating a short story called “Black Country” by Charles Beaumont, about a jazz musician who committed suicide, which got Playboy its first prestigious prize: Gold at the Chicago Art Directors Awards. In 1956, Neiman came up with his famous Femlin, a frisky, mostly-naked female figure, which he drew in many variants for Playboy throughout his life. In this exhibition, Nude with Mask (1985) appears unambiguous in its evocation of sexual pleasure.

Neiman’s 2012 passing in Manhattan, aged 91, was inevitably an occasion for assessing his place in the pantheon of great artists. The New York Times, in a front-page tribute, that included a color photograph of the artist, compared him to Norman Rockwell and Andrew Wyeth. Art historian Richard Brilliant located him in multiple traditions—Dutch and German artists in the 16th and 17th centuries, when popular prints were widely accepted and whose popular subjects in paintings fill our museums; Italian artists of the 18th and 19th centuries, who created works for an international clientele, depicting contemporary Italian life in the countryside, Rome and Venice—works which have been avidly sought ever since; and the Ashcan School, represented by Robert Henri, George Bellows and Reginald Marsh, who portrayed American life in works that fully captured the spirited, worthy engagement in the drama of daily life experienced by ordinary individuals. Richard Brilliant concluded in Five Decades:

Neiman’s formidable achievement is increasingly apparent. While much of the art world eschewed representative art, he created, depicted, and made his own an entire field, the spectacle of American public life and its delightful participation in the avid pursuit of paid leisure.

Neiman is indeed a pivotal figure who has given us one of the most important accounts of art and culture over the last six decades. Now that the art world acknowledges that the movement away from representative art was a detour rather than the one, true path, there can be no doubt that Neiman stands as one of the great artists of his time.

David Halle

Professor of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles

[image:LeRoy Neiman”Playboy Bunnies”(1966) Acrylic and Enamel on Board, 36 x 24 in.]

Media

Schedule

from May 17, 2014 to July 26, 2014

Opening Reception on 2014-05-17 from 18:00 to 20:00