"Stand Still Like the Hummingbird" Exhibition

David Zwirner 19th Street

This event has ended.

Much too simple, doubtless. But such is the nature of the real.... Ought we not first learn to fly backward too, or stand still in the air like a hummingbird? — Henry Miller

Stand still like the hummingbird, an exhibition curated by Bellatrix Hubert in the gallery’s 525 and 533 spaces, takes its title from a collection of short stories and essays by American writer Henry Miller, published in 1962. Known equally for his mysticism and dark humor, Miller proposed the idea of “flying backwards, standing still like a hummingbird” as a lighthearted antidote to the frantic pace of modern society.

In borrowing Miller’s title, the exhibition also embraces the paradox at its heart: the hummingbird, of course, only appears inert because we cannot visually process its wing beat quickly enough. Hubert has gathered a careful selection of paintings, sculptures, and videos by artists who engage with contradictions, impossibilities, and the absurd. They also share a concern with understated gestures and formal restraint, which finds its historical starting point in the exhibition with Marcel Duchamp’s Comb (1916/1964). Along with the artist’s other readymades from the early twentieth century, the gray steel comb signaled a dry, deadpan aesthetic, which came to influence a century of art-making. The works in the show are subtle iterations of this lineage, their matter-of-factness alternating between the poetic, funny, and unnerving.

Several works from the 1960s and 1970s, the decades where Duchamp gained renewed attention, provide apt examples of how straightforward gestures can be used to yield complex outcomes. Forty-two postcards by On Kawara, stamped by the time he got up on a given day and simply titled I Got Up (1968-1976), offer a map of the artist’s whereabouts that complement other projects in documenting and archiving his existence. Gordon Matta-Clark’s installation, Hair (1972), likewise offers a belated testament to the artist’s physical presence. Cut off on New Year’s Eve following a year of untamed growth, individual strands of his hair were carefully mapped out, numbered according to a three-dimensional grid, and arranged in a wig formation. Photographs document the ritualized performance like a taxonomy of change.

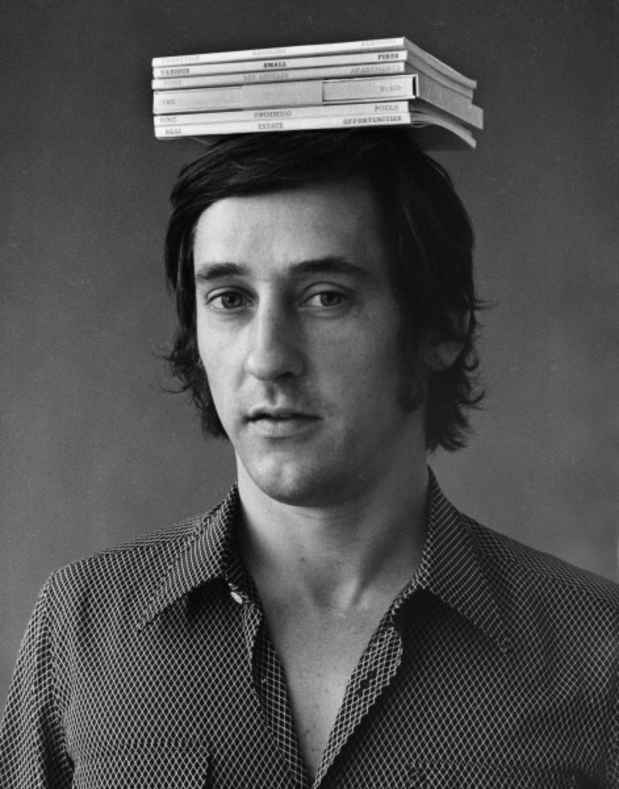

Other works forego reference to the personal altogether. They include Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Wassertürme (1967) and a collection of Ed Ruscha’s photobooks (1964-1978), which follow systematic rules for presenting everyday objects in a neutral (continue to next page) and objective manner. Mason Williams’s Bus Book (1967), a life-size, black-and-white silkscreen print of a Greyhound bus, adds a trompe l’œil dimension, but almost appears supernatural despite its candor. Its packaging in an unassuming, small cardboard box seems part of an intricate, tongue-in-cheek ploy.

Christopher Williams’s three photographs from 2008 follow similar rules for industrial photography adhered to by

photographers such as the Bechers, but manipulate viewers’ expectations in the process. With lengthy titles that list the name of the subject along with camera information, location, and details about the company that manufactured the subject’s shirt, they wryly “collage” together elements from the history of photography. Rodney Graham’s classically composed photographs of majestic oak trees shown upside-down play with the conventions of artistic representation while reminding us that the image projected onto the retina is, in fact, inverted, and subsequently corrected by the brain (Welsh Oaks, 1998).

Duchamp’s legacy is explicitly invoked by Sherrie Levine, whose appropriation of iconic Walker Evans photographs stretch the idea of the readymade to include existing artworks (After Walker Evans, 1981). The books and magazine cut-outs arranged on shelves by Carol Bove likewise fall under the category of readymades, and here derive multi-layered meanings from their careful composition next to one another.

Amongst the videos on view, three works by Morgan Fisher fuse the banal and the bizarre. In Red Boxing Gloves/Orange Kitchen Gloves (1980), the artist’s hands fondle kitchen and boxing gloves in soft motions that appear at once uncomfortable, erotic, and comical; in Protective Coloration (1979), layers upon layers of colorful disguise—fake teeth, goggles, swimming caps—gradually render Fisher unrecognizable as he silently faces the camera. A different type of uncanniness is provided in Bruce Nauman’s Raw Material with Continuous Shift-MMMM (1991), which incorporates an upside-down, revolving self-portrait that infers a sense of dizziness upon the viewer, while obstructing easy identification.

Francis Alÿs’s video Retoque/Painting (2008) shows him repainting by hand fading median strips on a road stretching across the Panama Canal. This mechanical, disciplined act calls attention to the mobility of geographical borders and the obliteration of territorial demarcations, while also presenting a tongue-in-cheek comment on the status of painting and the touch of the artist. Christopher Williams’s 5 1⁄2 hour long Supplement (2003) presents footage from a popular German cooking show without any editing, thus showing seemingly interminable views of bubbling soups and toasts in the making (including a 50 minute long view of a jelly dessert setting).

Abstract works in the exhibition, including paintings by Tomma Abts and Alan Uglow, handwoven linens by Ruth Laskey, and a triangular column by John McCracken adhere to a minimal language while they are also curiously suggestive, playful, and personal. Works by Cady Noland (Institutional Field, 1991) and Robert Gober (Untitled, 2000-2001) are balanced between abstraction and representation: Noland’s metal fence placed flat on the ground becomes an eerie aesthetic form, while Gober’s bronze cast of a block of Styrofoam presents a visual contrast between light and heavy, sculpture and pedestal. Hubert curated the critically acclaimed group exhibition a point in space is a place for an argument at the gallery in 2007. She has been a partner at David Zwirner since 2002, having joined in 1998.

Media

Schedule

from June 28, 2012 to August 03, 2012

Opening Reception on 2012-06-28 from 18:00 to 20:00

Artist(s)

Tomma Abts, Francis Alÿs, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Carol Bove, Marcel Duchamp, Morgan Fisher, Robert Gober, Rodney Graham, On Kawara, Ruth Laskey, Sherrie Levine, Gordon Matta-Clark, John McCracken, Bruce Nauman, Cady Noland, Jim Nutt, Thomas Ruff, Ed Ruscha, Alan Uglow, Christopher Williams, Mason Williams, Martha Wilson