"(Un)folding Patterns" Exhibition

Dorsky Gallery Curatorial Programs

This event has ended.

To many, mathematics and art could not stand on more different ground: one identifies with the left brain, the other with the right; one is analytical, the other creative, however “both disciplines are creative endeavors with analytical components that are essential elements of contemporary civilization" (Carla Farsi and Doug Craft, "One in Two, Two in One: Mathematics and the Arts," 2004,

This interest and the exploration of the connection between these two disciplines is the spark that led to the conception of this exhibition and is evident in the creative process of several of the participating artists, starting with Stephen Schaum, whose highly polished relief welcomes the visitors as they enter the gallery. For this exhibition, the artist created a multi-faceted wall relief made of highly reflective mirrored stainless steel, the surfaces of which he envisions as being ‘temporally activated’ by the path of the sun on a clear day: as sun rays hit the relief they will create blinding reflections which will overwhelm the senses of the viewers and create a feeling of displacement and groundlessness.

In the main gallery we’ll encounter a similar play on mirror and reflections, along with an interactive and playful element achieved through a low-tech and hands-on approach, in Susan Weinthaler’s BITS corner installation Echo. The bits are small wooden blocks outfitted with a magnet and then placed on a large sheet of metal. This simple mounting mechanism encourages audience’s participation and allows an infinite variable of compositions. In Echo, created specifically for this show, Weinthaler was inspired by the concept of infinity and the phenomenon of echo, rendered through a deconstructed portrait of the Greek nymph of the same name, combined with mirrors, the ideal medium to explore ideas of infinity.

Also driven by the idea of endless possibilities and the ever-changing reality of nature is the projection screened in the back room: a study for a new computational film elaborated by Michael Joaquin Grey. Computational physics, which provides digital representations of natural phenomena by solving their governing equations numerically, has transformed areas as diverse as scientific research, engineering design and film production. The starting point for this specific work is the history of aspect ratio and how essential its development has been in the history of film-making. Grey’s uses the rectangular shape of the classic 4:3 ratio, established by Thomas Edison in the late 19th century, sending it rotating in space to create endless spiraling configurations that remind us of an animation of a Serra drawing or the spinning of the black monolith in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In this high-tech/low-tech gap we can also place the Machine Drawings by NY-based visual artist and composer Tristan Perich. Perich is inspired by the aesthetics of math and physics, and works with simple forms and complex systems. His art and music are about simple forms and the intersection of randomness, order and composition. The Machine Drawings—pen on paper or wall drawings executed by a machine that he designed and built—use randomness and order as raw materials within a composition, and create works that are a combination of the delicacy of real drawings and the rigid, structured system of mechanics and code.

In his collages and sculptures, Stephen Talasnik’s connection to mathematical systems seems blatant, but is entirely fictional, with the artist inventing non-existing yet plausible formulas and engineering diagrams that he embeds in his 2-dimensional works. In Bernar Venet’s paintings from both his Equation and Saturation series, the artist depicts mathematical formulas on large canvases. The work exhibited in this show, Commutative Operation, was executed in 2001. Thomas Ruff’s works from the zycles series, of which one example is here exhibited, are also grounded in mathematics and physics, and show ‘computer screen-grab’ recordings of curves modeled in three dimensions. The views captured by the computer are produced as large-scale chromogenic prints, or are printed directly onto canvas.

A similar approach and aesthetic sensibility is found in Kysa Johnson’s drawing from the Subatomic Decay Pattern Pieces, a series of drawings of 11 of the most common subatomic decay patterns layered over and over each other. Subatomic decay patterns are the signature pathways that are created when unstable subatomic particles decay into other subatomic particles. The shapes of these pathways are determined by the mass, spin and charge of the particles involved in each decay. These marks are the most fundamental mark-making of the universe and are individually and collectively stunningly elegant. These pieces attempt to highlight the inherent beauty of the movement and architecture that lies at the base of all things.

R. Justin Stewart also explores and creates patterns in his drawings and sculptures from his Systems of Knowing series, one example of which is featured in the exhibition. Very much like patterns utilized by paper folders to create origami, Stewart makes two-dimensional detailed diagrams of what will become elaborate three-dimensional objects made with color-coded zip ties and o-rings; while the majority of zip ties are white, a few sculptures contain different colors to accent their forms. Inspired by the evolving interpretation of ideas, Systems of Knowing investigates how information is translated, transformed and conveyed across time and space. This series of installations investigates the interplay of information displayed through different frameworks.

Jane Philbrick’s sculpture, composed by twelve red spheres magnetically “floating” against a black panel, was born out of the collaboration with mathematicians, physicists and evolutionary biologists during the artist’s residency at MIT, and was inspired by Marta Pan’s 1961 Sculpture Flottante. After discovering preparatory sketches by the artist at the Skissernas Museum (Museum of Sketches) at the University of Lund, Sweden, Philbrick set to ‘recreate’ Pan’s sculpture by “illuminating the creative process” behind the work, instead of simply copying the final product.

Joe Diebes’ Technical Support is an interactive audio work created utilizing an algorithmic pattern designed by the artist. The viewer/listener is encouraged to dial a number and is prompted through what at first seems like a familiar set of options from an automated customer support center. The experience soon becomes labyrinthine—equal parts Escher and Kafka—drawing out the relations between the controlling language of corporate systems and the psychic disturbances associated with them.

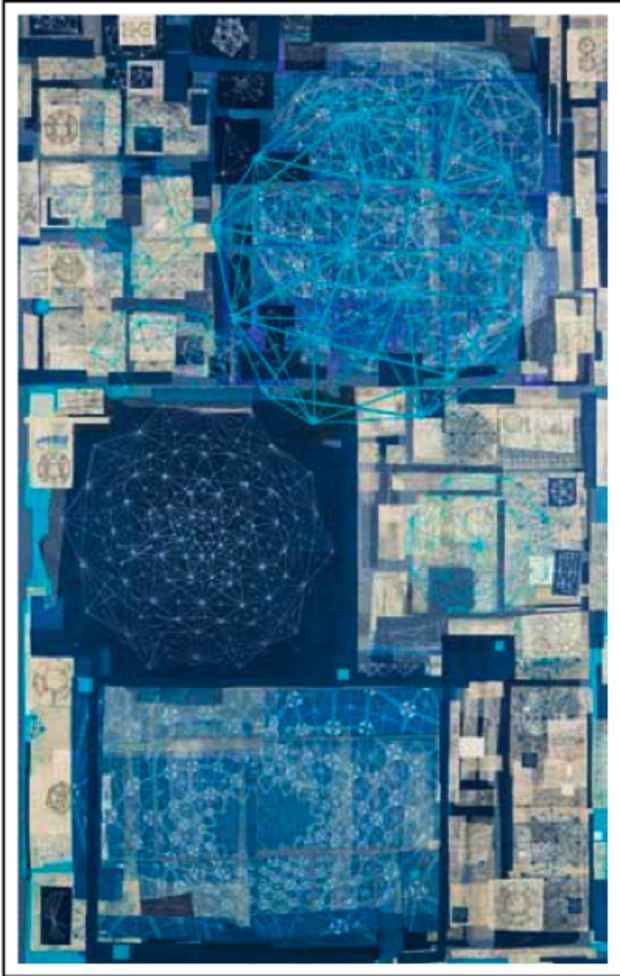

Vargas-Suarez Universal presents a wall installation featuring works from the Эльдорадо (El Dorado) series, abstract paintings on vacuumized aluminum thermal blankets on canvas and wall drawings based on the geometries of the architecture of the International Space Station, as well as Russian and American rockets and satellites. The paintings depict the geometries of the telemetry designs used for guidance, tracking and docking procedures, as well as the hardware associated with gyroscopes and other instruments forming avionics systems.

The exhibition concludes with three examples of Curved Crease Sculptures by MIT professors Dr. Erik Demaine and Dr. Martin Demaine, a father and son team of origami masters. Each sculpture in this series connects together multiple circular pieces of paper (between two and three full circles) to make a large circular ramp of total turning angle between 720° and 1080°. Erik and Martin Demaine’s works combine the art of origami with the science of geometric folding algorithms, a fitting conclusion for an exhibition that attempted to bring forth a rich mix of sensibilities towards art, abstraction, science, creativity, and meaning.

Media

Schedule

from May 20, 2012 to July 22, 2012

Opening Reception on 2012-05-20 from 14:00 to 17:00