Wang Keping Exhibition

Zürcher Gallery

This event has ended.

When Wang Keping made his first sculptures in 1978, he was twenty-nine and had never been to art school. Like all Chinese of his generation and social milieu – his father became famous in 1949 for having written the first novel on the Sino-Japanese War, his mother was a theatre and film actress – he fell victim to the turmoil of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. In 1966, while still at secondary scholl, he was conscripted into the Red Guards and later sent to northeastern China for a draconian process of “re-education”. With the return of a degree of political stability in the early 1970s, Wang, back from exile, set about finding his niche as an intellectual in a still tightly controlled society: first as a theater actor, then as a scriptwriter for government television. Nonetheless any hopes of creative freedom he might have had very quickly dashed, as everything he wrote was systematically turned down.

At the suggestion of an artist friend he tried his hand at painting , but dissatisfied with the results, he turned to sculpture – and discovered a mode of expression that suited him perfectly. Wood was a rare material in China, where afforestation projects never came to anything: the trees planted were cut down as soon as possible for fuel and building. His first sculpture, then, was carved out of a cross-piece from a chair. The works that follows were manifestoes against the absurdity, intolerance and violence of the regime, while theatre and literature were tied hand and foot to state structures, his chosen art form remained independent of officialdom and so provided him with a simple, direct, unfettered means of revolt against an unfree society. The late 1970s, however, were a relatively promising period: after Mao’s death in 1976 universities and libraries reopened, the Red Guards were rehabilitated and hopes for a more open and tolerant China blossomed. […]

This sense of urgency would bring a brief liberalization. In the spring of 1979 the authorities consented to the creation of a “wall of democracy” in Beijing for the expression of dissenting opinions. […] Wang, who had just finished his first sculptures, became one of the leading lights of a group of some twenty artists know as the Stars (Xing Xing in Chinese). Not only did this resolute band exhibit without official permission on the iron fence of the National Art Museum in Beijing in September 1979, they also demonstrated in the street for freedom of artistic expression on 1 October of the same year, the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. […]

Wang’s works were among the highlights of the wildcat exhibition, triggering astonishment, laughter and endless comment. The sculptures – Silence, Chain and others---which the artist hung on the fence of the National Art Museum, were caricatures and lampoons, kinds of press cartoons in 3D whose message came across at once. American journalist Fox Butterfield covered the event on the front page of the New York Times of 19 October 1979, together with a photo of Wang holding Silence, a head with its mouth and one eye sealed off.

Initially the authorities tried to hush things up, but the Star group enjoyed some support in high places and in August 1980 its members were allowed to show in two large halls in the same museum. In just over two weeks more than 100,000 people visited the exhibition, in which Wang’s sculpture Idol could only be interpreted as an irreverent portrait of Mao.

However, this phase of official wavering over how much rope to give the liberalization movement was not to last, and the full weight of the powers that be came down on the rebel artists. […] Some artists and intellectuals were imprisoned and others, deprived of all means of expressing themselves, saw only one solution: emigration. This was Wang’s choice in May 1984, after he had succeeded, despite endless official obstruction, in marrying a French woman who was then teaching at the university in Beijing. […]

So long starved of information about modern Western art, he wasted no time in visiting museums, first in France and then in the United States. Since then Wang had filled the gaps in his art education, but the remarkable thing about his approach is its continuing independence: it remains above all deeply embedded in his life history, in the Chinese artistic heritage of old---that of the Han period in particular---and in rural popular art. […]

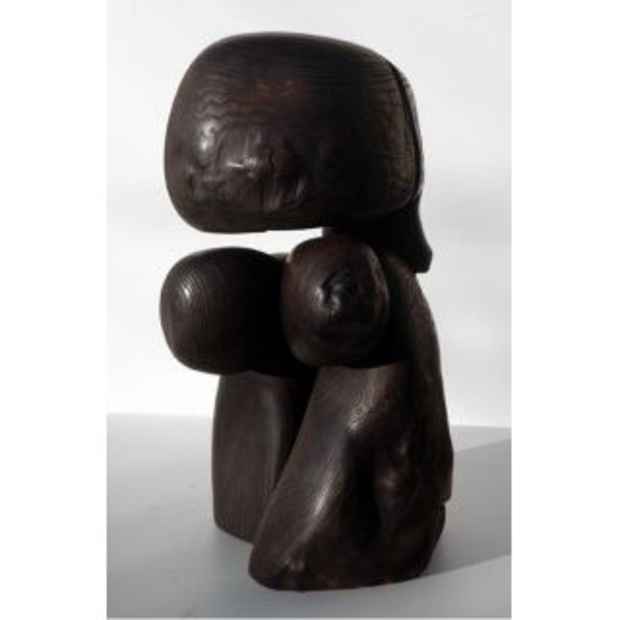

The resultant sculptures are at once ancient and modern, primitive---primal, even---and sophisticated, raw and subtle. His objective is an ongoing formal simplification and, as in those early works in China, his quest systematically leads his to trees, with all their knots and branches.

The move to France confirmed the direction he had already given his work before leaving China: to focus on a major theme---the female body--- already touched on in some of his Beijing pieces. The representation of nudity was forbidden in China. The female body---which he saw as the root of both the creative urge and representation---suggested to him the simple, solid, primeval forms he would render as sculpture. The female body and the tree he drew it from merged as life, energy, germination and growth.

In addition to this overriding concern, he offers a gallery of characters often betraying his sharp sense of caricature. He wittily presents some of them in pitiful or ridiculous postures, with a taste for certain personality types: the inept country bumpkin, the coquette---when his wood lends itself to the evocation of a plait or a chignon---and the bird who is the embodiment of all birds. These are the immediately identifiable silhouettes of figures from a palpable shadow theatre. […]

Wang is fond of referring to the carnality of wood. He intensifies this carnality with the sensitivity of his finishing touches: after being burned to obtain a colour that seems to permeate the entire figure, the surface of the wood is subjected to meticulous polishing that removes all toolmarks, rounds off the contours and provides the smooth, sensual look of a skin asking only to be caressed. Moreover the veins and fissures of the wood, taken into account at the outset and skillfully incorporated, play a large part in giving this skin a living look.

Clinging above all to the independence that underlies his profound originality, Wang has produced an oeuvre that seems atemporal, as if dating back to art’s very genesis. Yet he frankly acknowledges his deeply felt affinities with sculptors who are very much a part of Modernism, Brancusi the first among them. Wang admires the extreme formal simplicity the latter achieved, together with the concentration and detachment from reality demanded by the imagining and execution of works characterized, like his own, by purity and smoothness. He feels a rapport, too, with Zadkine, for those naked bodies critic Maurice Raynal famously praised for their “tender plasticity.”

Excerpt from: Sylvain Lecombre, (Zadkine Museum’s Director), Wang Keping , The Flesh of the Forests. Catalogue, Zadkine Museum, Paris (April

Media

Schedule

from March 26, 2011 to May 20, 2011

Closing Reception on 2011-05-04 from 17:00 to 20:00

film projection + fashion show